I have been spending to much time this semester putting out fires to really luxuriate in just how interesting my new city in the midst of a Sonoran desert can be.

I’ve been blown away by the diversity of stories and landscapes that I’ve discovered.

Years ago, I arrived in Cleveland, knowing nothing about the city or region, having been to the city once on a cross-country road trip with my college roommate. When I arrived, within weeks I was leading a media tour of the Cuyahoga River (using a HABS-HAER report as a guide) and later I learned about the city (and the Cultural Gardens) through my students.

So, this semester I’ve been working with students exploring the history and landscapes of Tempe, Phoenix, and Scottsdale. Early on, I had a TA to help me know the region, but after he moved on, I went back to first principles. I and my students engaged the region, its landscapes, discovering its peoples and places. Historians (and historians in training) too often send students to archives first. My approach has always been a bit different–to head into the city itself: to walk it, to talk to its people, to sense its contours.

Along the way, I’ve learned too much to recount here, including the repetitive and persistent flood of the desert–not something new with overbuilding but a natural aspect of the landscape. I’ve met archival geeks, discovered collections of photographs and documents, and engaged the community.

By early 2014, you will begin to see this work in Salt River Stories, the latest Curatescape project, as students and communities begin documenting themselves in ways that will transform how we view place in this region.

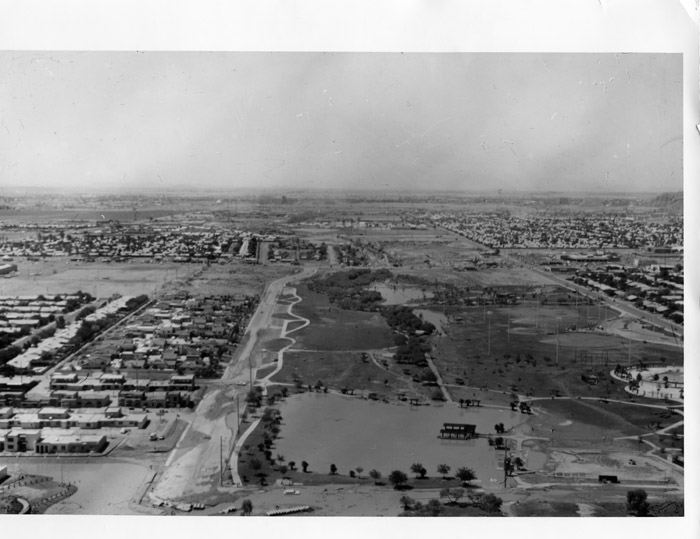

Just this week, I discovered a brilliant digital archive in the making at the Scottsdale Public Library, which had images that accentuated things I’ve been learning. For example, the flooding in the valley is remarkable, from flood irrigation, to bridges, to the many washes that dot the landscape (all but invisible to me as an outsider), as well as the urban riparian zones designed for flood control. Yes, that’s right. Imagine a 12-mile urban park flowing through the middle of a desert community that serves both as a green space (yes, it’s irrigated) and a wash during the monsoons. How creative, but who knew?

At the same time, I’ve been learning about Native American history through a student who wants to document his community in oral history, and whose recordings, ironically, are being held up by the IRB. Imagine that, an IRB process that prevents a Native American student from conducting interviews in his community, with folks lining up to talk to him. Anyway, I’ve been meeting his family and community informally; they have introduced me to an urban Native American community that is surrounded by Phoenix, in Guadalupe, Arizona. At the heart of the community is Our Lady of Guadalupe church and the “Cuarenta,” 40 acres of land developed by the local Yaqui Indian community. Wow, lots of great stories and insights; and an even more interesting landscape. How do you capture the sense of community that has been built, sustained, and expressed in a community plaza?

I had expected a Phoenix to be less varied–more suburban–than its been. Surely, there is much here that is cookie-cutter, but asking the simplest questions reveals a landscape of remarkable diversity. This landscape reveals a complexity that often occurs in suburbs, but that more traditional urban narratives overlook because they don’t fit any readily available narrative.